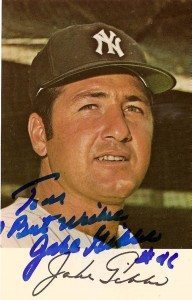

Catcher Jake Gibbs is a Yankee fascination. He chose baseball over football, spurred by a signing bonus topping $100,000. A star quarterback, he belongs to the College Football Hall of Fame. Giving even more back to Mississippi collegiate tradition, he coached Ole Miss baseball for 19 seasons.

He wore the Yankee pinstripes from 1962-71. Gibbs answered three questions with a kind hand-written response:

Q: What pressure did you feel after signing such a huge deal to play for the Yankees?

“A: I wasn’t the first bonus baby by the Yankees. Frank Leja. It wasn’t a big deal. I just went out and tried to play good baseball.”

(This is in contrast to Gibbs’ 1969 Topps card cartoon, which read: “The Yankees paid Jake a huge bonus to forget about football.” I told him the card read like a James Bond plot.)

Q: I can imagine some of the hard hits you endured as a quarterback. What were some of the toughest collisions you faced at home plate with the Yankees?

“A: I had many. I blocked the plate one night in KC, the old park, and got run over about the time I was catching the ball. Really popped my neck. The trainers rubbed me for two hours the next day. It was your job to protect the plate.”

Q: What were your first impressions of Thurman Munson?

“A: Thurman and I played together two years. We worked together very well. I tried to help him knowing the pitching staff. He was a great hitter with a real quick release to second base.

“We became good friends. I still think about him.”